Post updated 31.03.2025

In our previous post on the AI Act, we concluded with a remark concerning the AI Act and the GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation): Are the two regulations aligned, or are there contradictions?

In this post we want to explore this question.

NOTE: When speaking about personal data and data subjects in the following, it is in the context of the GDPR. In addition, our concerns about AI and GDPR are mainly directed at general-purpose AI systems (GPAI-systems) where large amounts of (scraped) data is used to train the GPAI-model on which the GPAI-system is built. (See box F below for exact definitions.)

The scope of the AI Act is comprehensive – it applies to any actor and user of AI systems within the jurisdiction of the European Union law, regardless of the actor’s country of residence.

As the GDPR, the AI Act is a regulation, contrary to a directive, which means that EU member countries have to implement it in their own legislation with only minor adaptive changes. The AI Act has EEA (European Economic Area) relevance as well, which means that the AI Act has to be implemented in Norwegian legislation – as the GDPR was.

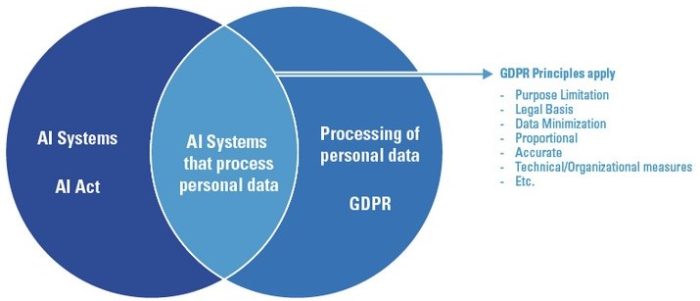

The diagram shown illustrates the situation: There are some obvious overlaps because AI systems may process personal data, and so GDPR principles apply.

On that basis, we could say “end of story” and “case closed”. However, there are some differences and potential conflicts, making it worthwhile to spend some time on the issue.

It is beyond the scope of this blog post to cover all aspects of the issue at hand, so let’s discuss the fundamentals, with what’s most relevant to Runbox in mind.

The basics

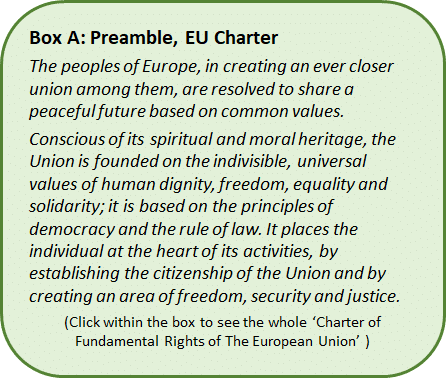

Both the GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation) and the AI Act (Artificial Intelligence Act) aim to secure data subjects the fundamental rights and freedoms as stated in the Charter of Fundamental Rights of The European Union.

You may ask, what are the objects or conditions that are at risk regarding AI? We’ll find the answer in the Preamble of the Charter, where the two first paragraphs are shown in Box A.

What’s at stake becomes clear by reading those two paragraphs.

The GDPR and the AI Act respond to the Charter differently. While the objective of GDPR is protection of personal data against misuse, the objective of the AI Act is protection against harmful effects of AI systems, but also supporting innovation.

There is another difference worth noticing:

- The AI Act applies to providers and users of AI systems in EU/EEA countries, regardless of national affiliation, personal data or not;

- The GDPR applies to controllers and processors residing anywhere, dealing with the processing of personal data (data subjects) related to data subjects residing in the EU/EEA area. (Article 3)

In summary: The AI Act is about AI/GPAI products available within EU/EEA and applies to all AI systems regardless of whether they process personal data; GDPR is about EU/EEA-citizen’s (data subject’s) right in relation to their personal data, regardless of the system’s purpose and where the processing take place.

The connection appears when AI systems use personal data, for instance for training purposes. More on that below.

Differences in scope, overlaps in application

Roles and Responsibilities

The central entity in the GDPR is the data subject, and any data that can be linked to this, i.e. personal data. Accordingly, the scope of the GDPR is protection of individuals’ privacy. A company that determines the purpose of processing of personal data is classified as a “controller” under the GDPR, while a company that processes personal data on behalf of the controller, is a “processor”.

The AI Act serves primarily as product safety regulation, i.e. to prevent that an AI-system will create any harm – that it is trustworthy, reliable, and aligned with ethical principles. It is notable that AI-systems must comply with the GDPR’s requirements like transparency, accountability, accuracy, integrity, data minimization, and lawful processing.

In the AI Act terminology, the actors are named “providers” and “deployers”:

- Providers/developers are both those who develop an AI model and AI system/GPAI model and GPAI system, and those who market such models and systems;

- Deployers/users are bodies who have implemented an AI system for their own purposes.

The GDPR roles and the AI Act roles will often overlap. Many AI systems are likely to process personal data, so AI providers and deployers in such cases must comply with both the AI Act and the GDPR. Since a provider of an AI-system most likely is the developer of the system, and thus decides the content of the corpus * established to train the system, the provider is a controller under the GDPR. This means that such organizations that use personal data in their AI system, must verify that they comply with both the GDPR and the AI Act.

*) Large and structured dataset used to make AI models to “understand” (train, teach) and generate language expressed as text, pictures, and sound. (We use quotes to express that AI models in principle are dumb.)

Documentation requirements

In the GDPR, if processing of personal data may create risks to the fundamental rights and freedom of individuals, a DPIA, Data Protection Impact Assessment, is required, as outlined in the GDPR Article 35. A DPIA is mandatory when processing sensitive (special categories of) personal data**.

**) Examples: Racial or ethnic origin, political beliefs or religious beliefs, genetic or biometric data, health data, sexual orientation, financial information, criminal convictions and offences.

AI systems with unacceptable risk are, in short, forbidden, and hefty penalties are waiting for those who develop and use systems for social scoring, manipulative practices, and systems using certain biometric parameters.

In the AI Act, for high risk AI systems, a FRIA, Fundamental Rights Impact Assessment, as described in the AI Act Article 27, is mandatory, and must be carried out ahead of deployment.

In many cases the DPIA and FRIA will be similar, and this is taken care of in the AI Act Article 27, where FRIA requirement could be met as a supplement to a DPIA.

Transparency obligations

The transparency issue in the GDPR is mainly about the data subject’s right to be informed of the purpose of the processing, its legal basis, the rights to insight into how the data is processed, to access and to rectification – and not the least, in the context of AI, the rights in relation to automated decision-making and profiling.

In the AI Act the transparency obligations to providers and deployers/users of GPAI systems is much wider, where enabling market operators as well as individuals to understand the AI systems’ design and use, is required. This applies in all circumstances, not only if the AI system provides automatic decision-making, as in the GDPR. And so, the AI Act reinforces and extends GDPR protections.

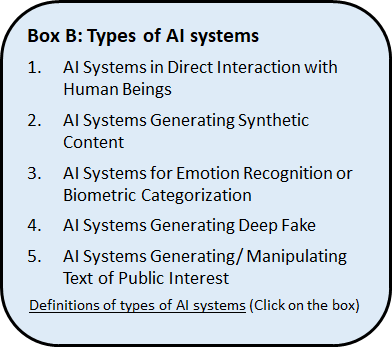

It would extend the scope of this blog excessively to go into details, but this link shows in brief transparency obligations specific to types of AI systems in box B, relevant for all AI systems. Overlap with the GDPR is significant especially for AI systems of type 3.

In the case of high risk AI systems (HRIAS),”[T]hey must come with clear instructions, including information about the provider, the system’s capabilities and limitations, and any potential risks”, among other requirements.

Lawful processing of personal data is dubious

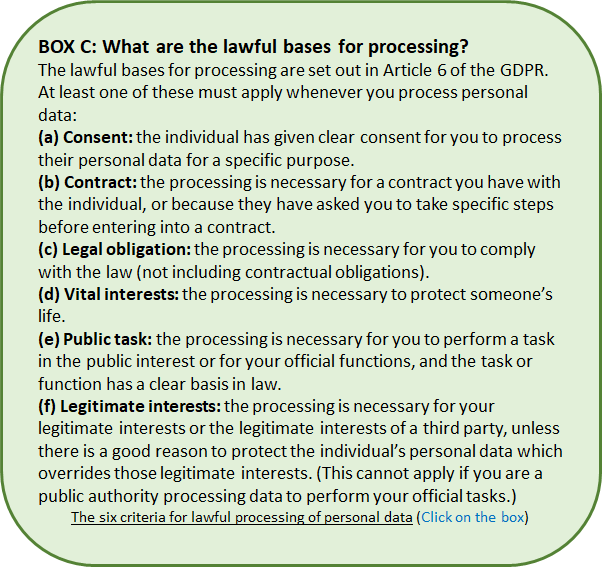

As mentioned above, the GDPR always applies when personal data is processed, that is, data related to a data subject, i.e. an identified or identifiable natural person belonging to the EU/EEA-area. So, if an AI model is to be trained with personal data involved, then a legal basis is required. The lawful basis for processing is given in GDPR Article 6, see box C.

Given that training of Large Language Models (LLMs) is the “art” of scraping the searchable Internet, it follows that those models contain personal data. It is easy to access data that is not behind a login page, and that means a lot might contain personal data. But personal data that was behind such walls in the first place, may have been pirated, and then published in the open – if other stronger security measures were not in place. In addition, data from AI companies might incorporate users’ interactions with chatbots. Personal data may include prohibited biometric data (in AI context) or restricted use of sensitive data (in GDPR context), which make data scraping even more dodgy.

It is very difficult to imagine how it will be possible for providers/developers of AI systems to obtain consent at all from persons that have their personal data scraped before AI-scraping became an issue. To secure consent ahead of scraping is practically a hopeless task. (The same issue is relevant regarding copyrighted material, but we will put that aside here.)

Purpose limitation, data minimization principles, and the ‘right to be forgotten’ are bound to be broken

The GDPR, Article 5, limits the right to collect and process personal data unless there is a clear specified, explicit, and legitimate purpose from the start. How scraping of data that includes personal data can ever comply with this, is a mystery.

It follows that the minimization principle also is on shaky ground, because this principle demands a known service or a specific purpose. The way AI systems operate, make compliance with this impossible.

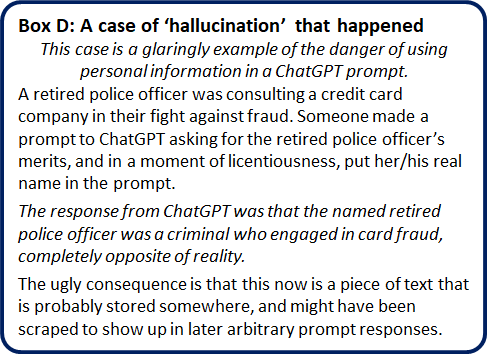

The ‘right to be forgotten’, or right to erasure (Article 17) is about the data subject’s right, under certain circumstances, to have their personal data deleted. Considering the way personal data in AI context could be used, this seems like an impossible task. When personal data may emerge as results of user prompts this difficulty is even more apparent — and more critical, especially with ‘hallucinations’ in mind, as exemplified in box D. – In this context, it should be mentioned that OpenAI in a blog post states that “When you use our services for individuals (our marking) like ChatGPT, DALL•E, Sora, or Operator, we may use your content to train our models.” One may opt out of training, but that is an extra process that could be felt burdersome.

The accuracy and storage limitation principles are at risk

The accuracy principle implies that personal data is to be maintained so that they are correct and accurate at all times, and the storage limitation principle implies that personal data should not be kept longer than is necessary for the purposes for which data is processed.

Since AI models’ use of personal data is disconnected from the original purpose, there is a substantial risk for breaching the GDPR, also in these regards.

What about integrity, confidentiality, and the accountability principles in the GDPR?

These principles are about preventing any intentional or unintentional risks, unauthorized or unlawful processing, unauthorized third-party access, malicious attacks, and exploitation of data beyond the original purpose. The accountability principle is about responsibility for compliance with all the above, and also to be able to demonstrate it through documentation of how compliance is achieved.

It seems easy to see that providers and users of AI systems will have big problems in this regard.

The training of AI systems is a problem in itself

AI systems, especially general purpose AI systems (GPAI) are dependent of vast amount of training data for their Large Language Models (LLM). This is based on ‘web scraping’, that is extracting data from websites by parsing and retrieving information from HTML or other structured web formats.

The scraping has become a huge business, and the generative AI tools like ChatGPT (OpenAI), Bard/Gemini (Google), Dall-E (OpenAI), and MetaAI (Meta) are fed enormous quantities of scraped training data. In addition, big-tech companies are updating their Terms of Service to allow the use of their users data for the same purpose. X/Twitter and Amazon have announced plans to use data from their users to train their AI.

Thinking about how much personal data there is on social media such as Facebook, LinkedIn, Reddit, YouTube (you name it), it is obvious that there is a huge amount of personal data available for scrapers.

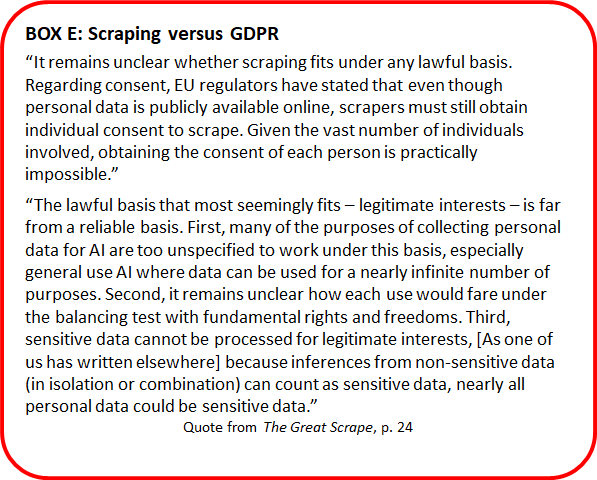

As we have written above, there is a lot of incompatibility regarding scraping of personal data and the GDPR, and “… the Dutch data protection authority Autoriteit Persoonsgegevens (AP) held that scraping of personal information is almost always a violation of the GDPR”.

Should scraping be forbidden?

With all these contradictions between the GDPR and the field that the AI Act will regulate, that is, GDPR versus GPAI, and the LLM, and the scraping which is fundamental for the GPAI to function, should scraping be forbidden? If so, the consequences will be formidable.

Under the GDPR, scraping that includes personal data, requires a lawful basis, that is either consent or legitimate interest, which constitute the most common lawful bases (see box C). In practice, to obtain consent seems impossible.

Legitimate interest that allows processing of personal data when “processing is necessary for the purposes of of the legitimate interest pursued by the controller or by a third party, except where such interests are overridden by the interests or fundamental rights and freedoms of the data subject which require protection of personal data, in particular where the data subject is a child.”, ref. Article 6(f), could probably be used for the purpose of LLM-training as such, but not when a GPAI-system produce arbitrary responses on an arbitrary prompt. In the case of sensitive personal data, the legitimate interests lawful basis is unavailable (Article 9).

“Currently, scraping is mostly a lawless realm, where hardly anything limits scrapers and where scrapers have virtually no responsibilities. Scrapers should be treated similarly to other organizations that collect and use personal data.” The Great Scrape

So, where do we stand? A ban on scraping is not feasible, but are there ways out of the incompatibility between data scraping/GPAI and GDPR? Such paths are not easy to see. The authors of The Great Scrape try to outline a consent model, regulatory means, principles, and guidelines for scraping, which we might refer to.

Precautionary steps

In the meantime, we as individuals can protect ourselves by being aware that information we post on social media and in ChatGPT prompts may potentially be scraped and end up on someone’s computer screen – maybe in a hallucination, like our unfortunate retired police officer in box D. And if that weren’t enough, AI systems like ChatGPT may use your content to train their models, unless you opt out, as OpenAI declare you can do.

Update: A grotesque example of ChatGPT-hallucinations was published by the Norwegian National Broadcasting (NRK) on March 20, referring to TechCrunch, about a Norwegian that has complained to the Norwegian Data Protection Authority because ChatGPT returned made-up information describing him as a murderer and accordingly a convict. – More details on the BBC and NOYB – European Center for Digital Rights.

Let’s also make a remark regarding Runbox’s website: Surely, our public websites are subject to be scraped by a number of web scrapers. This means that all information on our websites that is not protected by authentication most probably have ended up in a number of AI systems and search indices. When this probably is the case, since there is no personal or sensitive data on these pages, it shouldn’t be of any harm.

However, rest assured that all account information and account contents are safely protected by our multi-layered security wall, and they are therefore not scrapable and are accordingly safe from turning up in any AI system.

Independent of scraping, to add an extra layer of security we recommend that our users also activate Two-Factor Authentication (2FA) as described in our Help section (link to https://help.runbox.com/account-security/).

Postscript

The AI landscape is changing fast. Since our previous blog post “EU’s AI Act: What it is all about” we have seen new developments popping out: Deepseek (China), Gemini 2.0 (Google), Grok 3 AI model (xAI), ChatGPT 4.o (OpenAI/Microsoft) –- to mention a few.

This development underlines that it would be a hopeless task to try to regulate the development and use of AI systems with a law that is about technology. Instead, the AI Act use the risk for breach of EU/EEA citizens (data subjects) fundamental rights and freedoms as stated in the Charter of Fundamental Rights of The European Union. So, the approach from the EU regarding AI, has turned out to be a clever one..

But the implementation time frame for the AI Act to be in force may give companies room for developments that make it difficult for the AI Act to have effect. As is often the situation, laws and regulations have trouble keeping pace with technological advancements.

In recent news from the European Commission, and the Feb 11, 2025 speech of commission president Ursula von der Leyen, it is obvious that EU now is becoming aware that the AI Act may limit innovation, and cause the EU to fall behind the US and China when it comes to the use of AI.

Lastly, and for the record: It is worth mentioning that the proposal of Artificial Intelligence Liability Directive (AILD), aimed to address the difficulties individuals face in making liability claims for AI-induced harm, has been withdrawn from the European Commission work programme for 2025. But as stated in this article, EU Member States already have liability systems that can catch AI challenges in this respect.

Recommended reading

- https://dl.acm.org/doi/pdf/10.1145/3531146.3534642 Generative AI in EU law – Liability privacy intellectual property and cybersecurity – Nov 2024

- https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4884485 The Great Scrape – The Clash Between Scraping and Privacy – July 2024

- https://arxiv.org/pdf/2202.05520 What Does it Mean for a Language Model to Preserve Privacy – June 2022

- https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5031626 Learning from Europe: Utilising the EU AI Act’s Experience to Regulate Scraping-Based AI Models – August 2024

- https://www.edpb.europa.eu/news/news/2024/edpb-opinion-ai-models-gdpr-principles-support-responsible-ai_en EDPB opinion on AI models: GDPR principles support responsible AI – December 2024