This is blog post #19 in our series on the GDPR.

Runbox takes a clear stand against big tech companies’ use of personal information for advertising purposes, and we are critical of their huge influence on society in general.

At the same time, we are proud of the Norwegian government agencies’ effort to crack down on companies breaking privacy legislation, by applying the legislation provided by the EU’s GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation).

This monitoring of privacy has its roots as far back as 1978 when Norway, as the second country in the world (shortly after Sweden), adopted a law on the processing of personal data, and established Datatilsynet (the Norwegian Data Protection Authority; NDPA).

For instance, in October 2022 we wrote about Google Analytics (GA) vs privacy, following up with a blog post about action taken by NPDA towards a Norwegian company’s use of GA, which implies unlawful transfer of personal data to the United States via GA.

In 2021 we published a couple of blog posts about reports from Forbrukerrådet (the Norwegian Consumer Council; NCC) about how the extensive AdTech and MarTech industry use personal data for targeted advertising.

NDPA was then prompted (by NCC) to impose a fine of NOK 65 mill (approximately USD 6,5 mill) on the dating app Grindr for breaching the consent requirement in the GDPR. (Read our update on 30 September 2023 on the Grindr case here.)

The Norwegian DPA case against Meta – and personal data as a commercial product

Meta Platforms Ltd is the umbrella organization that owns Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, and more. Currently, the Norwegian DPA has a lawsuit going against Meta Platforms Ireland Ltd and Facebook Norway AS, because of illegal behavioral advertising where they use personal data they are not allowed to for such purposes [source, source] according to the GDPR.

When they (as do Google and other tech companies) are using personal data for targeted advertising, it creates plenty of opportunities for advertisers to pay and get your personal information in return. [source].

In addition, they share the access to users’ data with other tech firms when doing business together, for instance Facebook argues that such firms are essentially an extension of itself, defined as “service providers” or “partners” [source, source, source, source].

If that weren’t enough, real-time bidding (RTB) results in the average Norwegian internet user’s data being shared 340 times per day, according to a study from the Irish Council for Civil Liberties (ICCL) [source]. The fact that personal data has become commercial merchandise could be a theme for a separate blog post, but for now we’ll stick to what the headline indicates.

The NPDA has taken a leading role and has been involved in this legal issue for many years precisely because it has such major implications for Norwegians’ privacy. [Source: Datatilsynet]

Meta’s gliding flight for legal use of personal data in their advertising business

The NDPA versus Meta is the provisional culmination of a long process starting in May 2018, the day after GDPR came into force in the EU.

At that time the Austrian non-profit European Center for Digital Rights (NOYB) filed four complaints against respectively Google (Android), Facebook, WhatsApp and Instagram over “forced consent”: The services would not be accessible if users declined to agree to their terms of use [source], which is a breach of GDPR Article 6.

The complaint against Meta was lodged on 25 May 2018 to Österreichissche Datenschutzbehörde [source] who transferred the complaint to Facebook Ireland Ltd on behalf of the data subject from Austria.

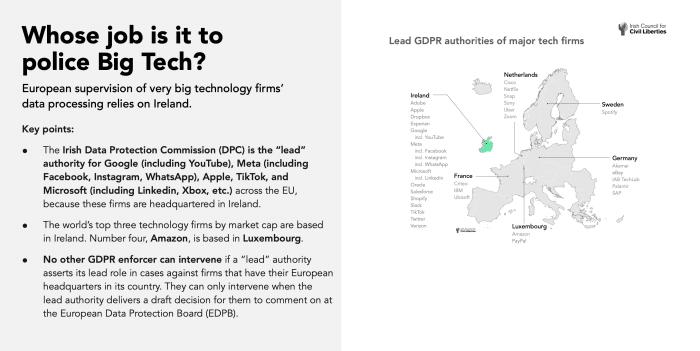

Because Meta’s regional headquarters in Dublin is serving European countries, it is the Irish Data Protection Commission (DPC) who is Meta’s lead European data privacy regulator (Lead DPA).

Since the NOYB’s complaints in 2018, the cases have been through the European Data Protection Board (EDPB) and the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU), where the conclusion is unanimous: Meta can’t use personal data for targeted advertising based solely on its Terms of Service (ToS). The GDPR’s Article 7, Recital 32, Recital 42, and Recital 47 make this very clear.

The apple of discord has been whether Meta uses the correct basis for processing personal information when they collect data about what users do on the platform, and use it to display targeted advertising. The dispute is about the term contractual necessity, legitimate interest, and consent, referring to GDPR Article 6.

Meta first argued towards the Irish DPC, that contractual necessity, as stated in Facebook and Instagram ToS from 2018 (after introduction of GDPR), was a sufficient legal basis for its advertising business – claiming that users of Facebook and Instagram are in contract with Meta to receive targeted ads. This actually means that Meta admits that behavioral advertising is a core service [source].

But after the ruling by EDPB 5 December 2022, and financial penalties totaling EUR 390 million from DPC 04 January 2023, Meta 5 April 2023 moved to “legitimate interest” in its ToS. The fines are set according to GDPR Article 83 and seem significant, but is a small amount compared to that the advertisement practices that helped Meta generate $118 billion in revenue in 2021.

The penalty of EUR 390 million was decided because the contractual necessity in Meta’s ToS as legal basis for targeted ads was deemed in violation of the GDPR. However, Meta’s move to argue legitimate interest did not help, even when Meta provided an “opt-out tool”. Under the GDPR Articles 21(1) and (2), users have the right to object to companies claiming that they have a “legitimate interest” in the processing of their personal data.

A new player in the field: Das Bundeskartellamt

Then on 7 February 2019, the German Federal Cartel Authority (“Bundeskartellamt”), with support from the German Consumer Rights Organization (“VZBV”), entered the arena. They brought into the game the German competition legislation with a decision arguing that Meta’s terms of use for Facebook violated German legislation due to the abuse of a dominant market position by Facebook merging and utilizing the data in user accounts.

Facebook’s terms were said to violate the GDPR, as using Facebook required that Meta could collect and process user data from various sources without actual user consent. On this basis Bundeskartellamt prohibits Facebook from combining user data from different sources — Facebook-owned services and third party websites included.

In the case between Germany and Meta that followed, the Higher Regional Court, Düsseldorf (Oberlandesgericht Düsseldorf), put the case forward to the CJEU which decided on 4 July 2023 that legitimate interest (referring to Article 6 (1f)) is not adequate for targeted advertising, and that the user’s explicit consent is necessary to be in line with the GDPR. With this, the CJEU agreed with noyb, and Meta is not allowed to use personal data beyond what is strictly necessary to provide its core social media products.

That said, the CJEU recognizes that legitimate interest may be used as basis for direct marketing processing, but this argument will not outweigh the interests and rights of individuals.

The Irish DPC is dragging its feet?

Here we have to mention that the Irish DPC has been unwilling to fully support the claim that Meta violates the GDPR regarding their targeting advertising. Instead, they (on 6 October 2021) in their draft decision, initially sided with Meta and put the light on Meta’s lack of transparency, and thereby violation of the requirements of the GDPR (Article 12 and 13c). According to this, the Irish DPC proposed a modest penalty of EUR 28–36 million.

Following the GDPR procedure, the draft decision was sent to the other DPAs within EU/EEA who may have a legal interest in the decision. Ten of 47 raised objections against the DPC’s reasoning that the personalized service could legally include personalized advertising. The disagreement led the Irisih DPC to refer the point of dispute to the EDPB.

As referred above, the EDPB took the view that Meta Ireland could not rely on contractual necessity as legal basis for their targeted advertising, and due to the binding decision by EDPB 5 December 2022, the Irish DPC had a month to reach a final decision.

The story didn’t end there, as is explained in the 12 January 2023 EDPB press release where the Irish DPC is instructed to issue a tenfold penalty increase – both because of lack of transparency and breach of the GDPR – on Meta Ireland to €210 million in the case of Facebook and €180 million in the case of Instagram [source]. The Irish DPC then had to follow the EDPB instruction as it did on 31 December 2022 regarding Facebook and Instagram.

In the binding decision the EDPB also directed the Irish DPC to conduct a fresh investigation into Facebook and Instagram regarding the different personal data they collect, hereunder to assess whether processing of sensitive data is taking place [source].

The Irish DPC did not agree and said that “the DPC considers it appropriate that it would bring an action for annulment before the Court of Justice of the EU in order to seek the setting aside of the EDPB’s directions” [source]. And so it has done. The details are not known per 23 March 2023 [source], but the claims probably refer to Article 263 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, which allows the CJEU to examine the legality of the legal acts of bodies, offices or agencies [source].

The Irish DPC has been criticized as a bottleneck of enforcement regarding GDPR cross-border complaints concerning the 8 big tech companies (Meta, Google etc.) that have their European headquarters in Ireland. According to the report by the Irish Council for Civil Liberties (ICCL), and adding the new cases since the report was published, some 80 % of all cases have been overruled by the EDPB with demands for tougher enforcement action.

Back in 2020 the Austrian non-profit European Center for Digital Rights (NOYB) filed an open letter to the EU authorities that brought the Irish DPC’s weaknesses to light, referring to secret meetings between Meta and the Irish DPC to find ways to bypass GDPR requirements [source].

For the sake of balance we will refer to an article in The Irish Times where The Irish Data Protection Commissioner Helen Dixon defended the work of the DPC, and rejected claims that Ireland is a ‘bottleneck’ for enforcement [source].

The Norwegian DPA is taking action and imposes daily fines

The Irish DPC’s delay in the Meta case has triggered the Norwegian Data Protection Authority to intervene: On 14 July 2023, the Norwegian DPA notified Meta that they may decide to impose a coercive fine of up to NOK 1 000 000 (approximately USD 100 000) per day because of non-compliance with the GDPR’s Article 6, which in this case requires consent (ref. Article 6 (a)). Meta had until 4 August 2023 to either stop the use of personal data or receive daily fines.

On 4 August 2023 the NDPA put a temporary ban on Meta’s processing practice to use behavioral marketing. “Temporary” meant three months (from 4 August 2023), or until Meta showed that they had legally aligned themselves. That didn’t happen, the time limit was exceeded, and the NDPA did what they warned Meta about on 4 August by imposing a coercive fine of NOK one million per day [source], starting on 14 August, lasting until 3 November 2023.

It may seem strange that the NDPA can do this since Meta has its European headquarters in Dublin, and normally it is the Irish Data Protection Commission as Lead DPA that supervises the company in the EEA.

However, since NDPA’s concern is Norwegian users, they did this with reference to the GDPR Article 66 which allows data authorities to enact measures immediately when “there is an urgent need to act in order to protect the rights and freedoms of data subjects.” NDPA asked the Irish Data Protection Authority to impose a ban in May, but they didn’t, without saying why [source].

It follows that he decision from the Norwegian Data Protection Authority only applies to users in Norway.

Meta is taking the NDPA decision to Oslo District Court – and lost

It was no surprise that Meta didn’t accept the ban, and their reaction was to take the ban and the fine to Oslo District Court on 4 August 2023) , applying for a temporary injunction in an attempt to invalidate the decision. The reason: “This decision is invalid and causes significant damage to the company” [source].

“Meta Ireland and Facebook Norway have further stated that the decision is disproportionate, unclear, impossible to fulfill, contrary to other legislation (including the European Court of Human Rights, ECHR), and that it has already been fulfilled” [from the court’s ruling]. None of these statements were given weight, and Meta lost according to the court’s judicial ruling 6 September 2023.

In the court Meta stated that they would have to suspend Facebook and Instagram services in Norway to comply with the order. This seems strange, because in a blog post update 01 August 2023 they announced the following:

“Today, we are announcing our intention to change the legal basis that we use to process certain data for behavioral advertising for people in the EU, EEA and Switzerland from Legitimate Interests to Consent.”

It is to be noted that the UK is excluded, Norway is not mentioned, and not a word is said about when and how the change will take place (more on this below).

In addition to the case in the legal system, Meta has submitted several administrative complaints against the Norwegian Data Protection Authority’s decision. These processes are ongoing. [Source: NDPA won against Meta]

NDPA asks EDPB to make the ban permanent, also for the EU/EEA area

The Norwegian DPA is only authorized to make a temporary decision in this case, and the decision expires on 3 November 2023. Because of the urgency as stated by NDPA, they, according to a press release 28 September 2023, have asked the central European Data Protection Board (EDPB) for a European binding decision in the case against Meta.

In the request, the NDPA asked that the Norwegian temporary ban on behavioral advertising on Facebook and Instagram be made permanent and extended to the entire EU/EEA.

Referring to Meta’s announced intention to change the legal basis to consent, NDPA says in the press release: “It is uncertain whether and when a valid consent mechanism may be in place. The Norwegian DPA believes that we cannot tolerate illegal activity in the meantime.”

It is just about one month until the Norwegian ban expires, and one can only await the EDPB decision. It would seem strange if the EDPB decides against making the ban permanent, and that it is preferable that the GDPR should be interpreted consistently throughout the EU/EEA, and the rest of Europe as well.

Meta’s last move: “Pay for your Rights”

In September this year Meta proposed to GDPR regulators that they want to charge Europeans monthly subscriptions if they don’t agree to let the company to expose them to targeted advertising.

According to Wall Street Journal on 3 October, Meta hopes to roll out the plan – Subscriptions No Ads (SNA) – in the coming months for Europeans users. This will hit users with fees in the range of EUR 10 to 20 per month depending on platform used and also if the accounts covers mobile devices.

With this, Meta is trying a smart move to circumvent requirements for explicit consent before processing user data to select ads that are targeted. The company refers to some other companies, such as Spotify, who offers users a choice to avoid ads for a paid subscription. But there is a difference, as Techcrunch points out: Spotify has to pay to license the songs it delivers ad-free to subscribers, while Meta gets content from its users for free.

In addition, Meta has pointed to paragraph 150 in the recitals of CJEU’s 4 July 2023 decision that “… if necessary for an appropriate fee…” could be an alternative to users who decline to let their data be used for ad-targeting purposes, and that opens the door to a subscription service. However, as NOYB points out, these 6 words are not directly related to the case and should not be part of the binding decision – and as Max Schrems, founder and chair of the NOYB put it (quote):

“The CJEU said that the alternative to ads must be ‘necessary’ and the fee must be ‘appropriate’. I don’t think € 160 a year is what they had in mind. These six words are also an ‘obiter dictum‘, a non-binding element that went beyond the core case before the CJEU. For Meta this is not the most stable case law and we will clearly fight against such an approach.” (our text highlighting)

Per 3 October it is not clear if the Irish DPO will deem the SNA-plan compliant with the GDPR, and it is also a question whether the CJEU will stick to its ruling from 4 July 2023.

Here it is also worth mentioning that Meta’s advertising network will fall under the EU’s Digital Markets Act which requires user consent before mingling user data among its services, or combining it with data from other companies [source].

The case of Meta vs GDPR will obviously roll on.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter, and Runbox take no responsibility for its accuracy. It is advised that when using the information for any purpose other than personal that the sources provided are verified. Expert advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.

ADDENDUM: Why is it urgent to stop behavioral advertising?

Behavioral advertising one of the largest risks to privacy: Statement from Datatilsynet

“Meta, the company behind Facebook and Instagram, holds vast amounts of data on Norwegians, including sensitive data. Many Norwegians spend a lot of time on these platforms, and therefore tracking and profiling can be used to paint a detailed picture of these people’s private life, personality, and interests.

Many people interact with content such as that related to health, politics and sexual orientation, and there is a danger that this is indirectly used to target marketing to them.

“Invasive commercial surveillance for marketing purposes is one of the biggest risks to data protection on the Internet today”, head of international department at the NDPA Tobias Judin says.

When Meta decides which advertisements will be shown to a user, they also decide what not to show someone. This affects freedom of expression and freedom of information in a society. There is a risk that behavioral advertising strengthens existing stereotypes or could lead to unfair discrimination of various groups.

Behavioral targeting of political adverts in election campaigns is particularly problematic from a democratic perspective. Since tracking is hidden from view, most people find it difficult to understand.

There are also are many vulnerable people who use Facebook and Instagram that need extra protection such as children, the elderly, and people with cognitive disabilities.”