This is blog post #18 in our series on the GDPR.

“Don’t tell anything to a chatbot you want to keep private.” [source]

Writing about AI in general and about chatbots specifically is like shooting at a moving target because of the speed of development. However, at Runbox we are always concerned about privacy and must examine the chatbots case in that respect.

Due to its popularity, we have mainly used ChatGPT from OpenAI as the target of our examination. NOTE: ChatGPT and the images from text captions DALL-E are both consumer services from OpenAI.

This blog post is a summary of our findings, leading to advice on how to avoid putting your privacy at risk when using the Natural Language Processing (NLP)-based ChatGPT.

Our examination is based on OpenAIs Privacy Policy, Terms of Use, and FAQ, and a number of documents resulting from hours of Internet browsing.

The blog post consists of two parts: PART I is a summary of our understanding of the technology behind language models in order to grasp the concepts and better understand its implications regarding privacy. In PART II we mainly discuss the relevant privacy issues. It is written as a stand alone piece, and can be read without necessarily have read PART I.

PART I: Generative AI technology

The basics

GPT stands for Generative Pre-trained Transformer, and GPT-3 is a 175 billion parameter language model that can compose fluent original writings in response to a short text prompted by a user. The current version of ChatGPT is built upon GPT-3.5 and GPT-4 from OpenAI.

ChatGPT was launched publicly on November 30, 2022. ChatGPT was released as a freely available research preview, but due to its popularity, OpenAI now operates the service on a freemium model [source].

The GPTs are the result of three main steps: 1) Development and use of the underpinning technology Large Language Models (LLMs), 2) Collection of a very large amount of data/information, and 3) Training of the model.

Let us also keep in mind that all this is possible only because of today’s advancements of computational power.

Language models

A language model is a system which denotes mathematics “converted” to computer programs that predict the next word/words in a sentence, or a complete sentence, based on probabilities. The model is a mathematical representation of the principle that words in a sentence depend of the words that precede them.

Since computers basically can only process numbers (in fact only additions and comparisons), text input to the model (prompts) must be converted to numbers, and likewise the output numbers have to be converted to text (response). Text in this context consists of phrases, single words, or parts of words called tokens.

When prompting a GPT then, your query is converted to tokens (represented by numbers), and used by the transformer where its attention mechanism generates a score matrix that determines how much weight should be put on each word in the input (prompt). This is used to produce the answer to the prompt, using the model’s generative capability – that is to predict the next word in a sentence by selecting relevant information from the pre-processed text with high level of probability of being fluent and similar to human-like text [source].

The learning part of the model is handled by a huge number of parameters representing the weights and also statistical biases for preventing unwanted associations between words. For instance, GPT-3 has 175 billion parameters, and GPT-4 is approximated to have around 1 trillion.

(The label “large” in LLM refers to the number of values (parameters) the model can change autonomously as it learns.)

Collecting the data

The texts the GPT model generate stems from OpenAIs scraping of some 500 billion words (in the case of GPT-3, the predecessor for the current version of ChatGPT) systematically from the Internet: books, articles, websites, blogs – all open and available information, from libraries to social media – without any restriction regarding content, copyrights or privacy.

The scraping includes pictures and program codes as well and is filtered resulting in a subset where “bad” websites are excluded

The pre-training process

All that data is fundamental for pre-training the model. This process analyses the huge volume of data (the corpus) for linguistics patterns, vocabulary, grammatic properties etc. in order to assign probabilities to combinations of tokens and combinations of words. The aforementioned transformer architecture is used in the training process, where the attention mechanism makes it possible to capture the dependencies between words independent of their position in a sentence.

The result of the pre-training process is an intermediate stage that has to be fine-tuned to the specific task the model is intended for, for instance providing texts, program code, or translation of speech as response to a prompt. The fine-tuning process uses appropriate task-specific datasets containing examples typically for the task in question, and the weights and parameters are adjusted accordingly.

Of cause, a ChatGPT-response to a prompt is not “burdened” with the ethical, contextual, or other considerations a human will perform. To prevent undesired responses (toxicity, bias, or incorrect information), the fine-tuning process is supervised by humans in order to correct inappropriate or erroneous responses, using prompt-based learning. Here the responses are given a “toxicity” score that incorporates human feedback information [source].

ChatGPT usage training

The learning process continues when response generated following by a user’s prompts is saved and subject to the training process, at least for 30 days, but “forever” if chat history isn’t turned off. In any event it is not possible to delete specific prompts from user history [source], only entire conversations

In the world of AI and LLMs, hallucinations are the word used when responses are like “pulled from thin air”.

OpenAI offers an API that makes it possible for “anyone” to train GPT-n models for domain specific tasks [source], that is to build a customized chatbot. In addition, they have launched a feature that allow GPT-n to “remember” information that otherwise will have to be repeated [source, source].

Takeaways

- The huge volume of data scraped is obviously a cacophony of contents and qualities that will affect the corpus and so also the probability pattern and the responses produced [source].

- ChatGPT has limited knowledge of events that have occurred after September 2021, the cutoff date for the data it was trained on [source].

- The response you get from ChatGPT to your prompt is based on probabilities, and as such you have no guarantee of the validity [source].

- A prompt starts a conversation, unlike a search engine like DuckDuckGo and Google that gives you a list of websites matching your search query [source].

- ChatGPT uses information scraped from all over the Internet, without any restrictions regarding content, copyrights, or privacy. However, manual training of a model was introduced to detect harmful content [source]. Violations of copyrights has resulted in lawsuits [source], and also signing of more than 10 000 authors of an open letter to the CEOs of prominent AI companies [source].

- Your conversation is normally used to train the models that power ChatGPT, unless you specifically opt-out [source].

PART II: Chatbot privacy considerations

The privacy considerations with something like ChatGPT cannot be overstated” [source]

The following introduction is mainly made for readers that have skipped this blog post PART I.

Generative AI systems, such as ChatGPT, use information scraped from all over the Internet, without permissions nor restrictions regarding content, copyrights, or privacy (more on this in PART II). This means that what you have written on social media, blogs, comments on an article online etc. may have been stored and used by AI companies to train their chatbots.

Another source for training of generative AI systems is prompts, that is information from users when asking the chatbot something. What you ask ChatGPT, the sentences you write, and the generated text as well, is “taken care of” by the system and could be available for other users through the answer of their questions/prompts.

However, according to Open AI’s help center article, you can opt-out of training the model, but “opt-in” is obviously default.

So, both the Internet scraping and any personal information included in your prompts can have as result that personal information could turn up in a generated answer to another arbitrary prompt.

This is very problematic for several reasons.

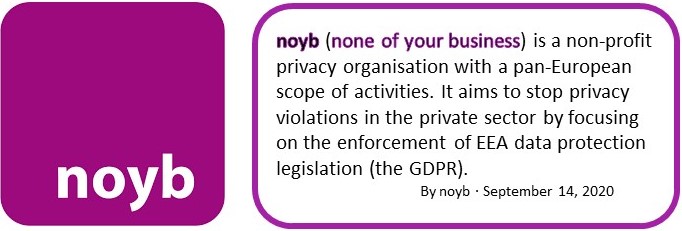

Is Open AI breaching the GDPR?

First, OpenAI (and other scraping of the Internet) never asked for permission to use the collected data, which could contain information that may be used to identify individuals, their location, and all kinds of sensitive information from hundreds of millions of Internet users.

Even if Internet scraping is not prohibited by law, it is ethically problematic because data can be used outside the context in which it was produced, and so can breach contextual integrity, which has de facto been manifested in the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) Article 6, 1 (a) as prerequisite for lawful processing of personal data:

…the data subject has given consent to the processing of his or her personal data for one or more specific purposes

Here language models, like Open AI’s ChatGPT, are in trouble: Personal data can be used for any purpose – a clear violation of Article 6.

Second, there is no procedures given by Open AI for individuals to check if their personal data is stored and thereby can potentially be revealed by arbitrary prompt, and far less can data be deleted by request. This “right to erasure” is set forth in the GDPR Article 17, 1:

The data subject shall have the right to obtain from the controller the erasure of personal data concerning him or her without undue delay …” on the grounds that “(d) the personal data have been unlawfully processed

It is inherent in language models that data can be processed in ways that are not predictable and presented/stored anywhere, and therefore the “right to be forgotten” is unobtainable.

Third, and without going into details, the GDPR gives the data subjects (individuals) regarding personal data the right to be informed, the right of access, the right to rectification, the right to object, and the right to data portability. It is questionable if generative AI systems can ever accommodate such requirements since an individual’s personal data could be replicated arbitrarily in the system’s huge dataset.

Fourth, Open AI stores all their data, including personal data they collect, one way or another, on servers located in the US. That mean they are subject to the EU-US Data Privacy Framework (see our blog Privacy, GDPR, and Google Analytics – Revisited), and the requirements set there.

To answer the question posed in the headline of this paragraph, Is OpenAI breaching the GDPR?It is very difficult to understand how ChatGPT, and other language models for generative use (Generative AI systems) as well, can ever comply with the GDPR.

What about the privacy regulations in the US?

Contrary to the situation in Europe, there is no federal privacy law in the United States – each state has their own jurisdiction in this area. There are only federal laws such as HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) and COPPA (Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act) which regulate the collection and use of personal data categorized as sensitive. However, there are movements towards regulation of personal information in several states as tracked by IAPP (The International Association of Privacy Professionals).

How do OpenAI use data they collect?

When signing up to ChatGPT, you have to agree to OpenAI’s Privacy Policy (PP), and allow them to gather and store a lot of information about you and your browsing habits. Of course, you have to submit all the usual account information, and to allow them to collect your IP-address, browser type, and browser settings.

But you also allow them to automatically collect information about for instance

“… the types of content that you view or engage with, the features you use and the actions you take, as well as your time zone, country, the dates and times of access, user agent and version, type of computer or mobile device, and your computer connection”.

All this data made it possible to build a profile of each user – bare facts, but also more tangible information such as interests, social belongingness, concerns etc. This is similar to what search engines do, but ChatGPT is not a search engine — it is a “conversational” engine and as such is able to “learn” more about you depending on what you submit in a prompt, that is, how you engage with the system. According to their PP and the citation above, that information is collected.

The PP acknowledges that users have certain rights regarding their personal information, with indirect reference to the GDPR, for instance the right to rectification. However, they add:

“Given the technical complexity of how our models work, we may not be able to correct the inaccuracy in every instance.”

OpenAI reserves the right to provide personal information to third parties, generally without notice to the user, so your personal information could be spread to actors in OpenAI’s economic infrastructure and is very difficult to control.

Misuse of your personal information – what are the risks?

It is reasonable to assume that OpenAI will not knowingly and willfully set out to abuse your personal information because they have to adhere to strict regulations such as GDPR, where misuse could result in fines of hundreds of millions of dollars.

The biggest uncertainty is linked to how the system responds to input in combination with the system’s “learning” abilities.

If asked the “right” question, the system can expose personal information, and may combine information about a person, e.g. a person’s name, with characteristics and histories that are untrue, and which may be very unfortunate for that individual. For instance, asking the system something about a person by name, can result in an answer that “transforms” a credit card fraud investigator to be a person adhered to credit card scam.

Takeaways

Using generative AI systems, for example ChatGPT, is like chatting with a “black box” – you never know how the “box” utilizes your input. Likewise, you will never know the sources of the information you get in return. Also, you will never know if the information is correct. You may also receive information about other individuals that you shouldn’t have, potentially even sensitive and confidential information.

Similarly, other individuals chatting with the “box”, may learn about you, your friends, your company etc. The only way to avoid that, is to be very careful when writing your prompts.

That said, OpenAI has introduced some control features in their ChatGPT where you can disable your chat histories through the account settings – however the data is deleted first after 30 days, which means that your data can be used for training ChatGPT in the meantime.

You can object to the processing of your personal data by OpenAI’s models by filling out and submitting the User Content Opt Out Request form or OpenAI Personal Data Removal Request form, if your privacy is covered by the GDPR. However, when they say that they reserve the right “to determine the correct balance of interests, rights, and freedoms and what is in the public interest”, it is an indication of their reluctance to accept your request. The article in Wired is recommended in this regard.

Valuable sources

- GPT-3 Overview. History and main concepts (The Hitchhiker’s Guide to GPT3)

- GPT-3 technical overview

- Transformers – step by step explanation

- LMM training and fine-tuning

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.

Continue Reading →