To all of our customers – thank you. Whether you’ve been with us from the start or have just joined the Runbox community, we’re truly honored that you have chosen us. It is your trust and loyalty that make our work possible.

To all of our customers – thank you. Whether you’ve been with us from the start or have just joined the Runbox community, we’re truly honored that you have chosen us. It is your trust and loyalty that make our work possible.

Our personal information is a valuable commodity, and privacy policies have become an essential part of the online landscape. But for most users, privacy policies are a maze of legal jargon, dense paragraphs, and complex terms. These policies often obscure how our data is being used. Instead of clarifying the truth, they make it hard for consumers to fully understand what they’re agreeing to.

In today’s digital world, email phishing scams are one of the most common and dangerous threats to individuals and businesses. These deceptive emails attempt to trick recipients into revealing personal information, clicking on malicious links, or downloading harmful attachments. Phishing attacks can lead to identity theft, financial loss, and even security breaches for organizations. For Runbox users, these scams can specifically target your email account and compromise your sensitive data. But by staying vigilant and following a few key practices, you can protect yourself from these scams.

At Runbox, we believe in a world where our digital communications can have a positive impact on the environment. Our mission is to reduce energy consumption and minimize our ecological footprint, both as an organization and as individuals. We believe that every action, including sending an email, should contribute to a sustainable future. By choosing Runbox, you’re not just using a secure email service – you’re making a conscious choice to support sustainable practices and contribute to the protection of the planet.

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has released a report exposing how Big Tech companies are overstepping privacy boundaries in their quest for user data. The report reveals the massive amount of personal information these companies collect, store, and profit from. Often, this is done without clear user consent or transparency. As concerns over data privacy grow, the report highlights the urgent need for stronger regulation and more responsible data practices.

In this blog post, we’ll break down the key findings of the FTC’s report and discuss how this overreach affects your privacy, along with what actions you can take to protect your data.

The FTC’s report, titled “A Look Behind the Screens: Examining the Data Practices of Social Media and Video Streaming Services” offers an in-depth look at how major technology companies, including Facebook (Meta), Google, Amazon, and others, are handling your personal data. Below are some of the major findings:

(more…)Social media platforms like Meta (Facebook, Instagram) and X (Twitter) are huge parts of our online lives. They’re where we catch up with friends, get our news, and share ideas. But while these platforms bring us together in a lot of ways, they also come with big problems—especially when it comes to privacy and misinformation. For a company like Runbox, being part of these platforms just doesn’t make sense. Here’s why.

Malware poses a significant threat to our personal information and security. From ransomware to keyloggers, malicious software programs can infiltrate our devices and compromise our most sensitive data, including contact lists. In this post, we’ll explore how malware works, the risks it presents, and the potential consequences of a breach.

We live in an era of constant digital surveillance, where governments and corporations collect vast amounts of personal data. Privacy has become one of the most pressing issues for people around the world. From targeted ads to government surveillance programs, personal information is constantly at risk. Protecting that privacy is not just a matter of convenience — it’s essential to safeguarding our freedoms, security, and autonomy. Runbox’s base in Norway plays a pivotal role in safeguarding your personal information.

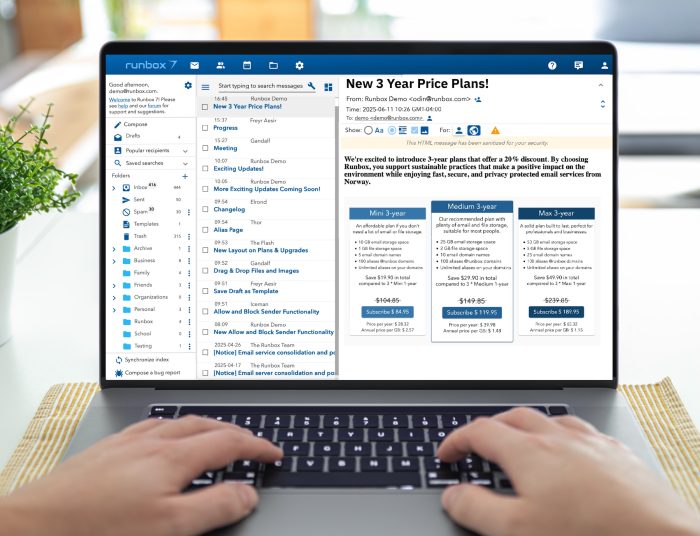

Runbox is dedicated to providing sustainable email services from the heart of Norway, where strict privacy regulations safeguard your data. We’re excited to introduce 3-year plans that offer a 20% discount. By choosing Runbox, you support sustainable practices that make a positive impact on the environment while enjoying fast, secure, and privacy protected email services from Norway.

We pride ourselves on delivering premium email services at an affordable price. In fact, we have not increased our prices since our company’s inception, and at the same time we have added substantial storage to all our plans. In a time when price hikes on essential services have become the norm, we believe in offering you predictability and stability for a service as vital as email.

(more…)In today’s digital world, privacy and security are more important than ever. As we navigate online communications, it’s important to understand how encryption can safeguard our emails. Let’s explore what encryption is, how it works, and why you want to consider using it.

When you send an email without encryption, it’s like sending a private message on a postcard – anyone who handles it can read its contents. At its core, encryption works by converting the readable data of an email into a scrambled format. Basically, the contents of that email turns into gibberish so that nobody can read it. The point is to keep the email private while it’s in transit from you to the recipient.

Even though most email services use some form of encryption for data in transit, this is not the same as end-to-end encryption. With end-to-end encryption, only the sender and the recipient can read the message. This method effectively prevents anyone else, including email providers, from accessing the content of your messages.

While many of us might feel that we have little to hide and aren’t overly concerned about others reading our communications, it’s important to understand how our information could be accessed. Encryption helps to safeguard our personal information, which may contain sensitive details about our personal finances, family matters, or other private information.

(more…)